Risking his life to tell us the truth about the oil industry’s “eco-cide” in South Sudan

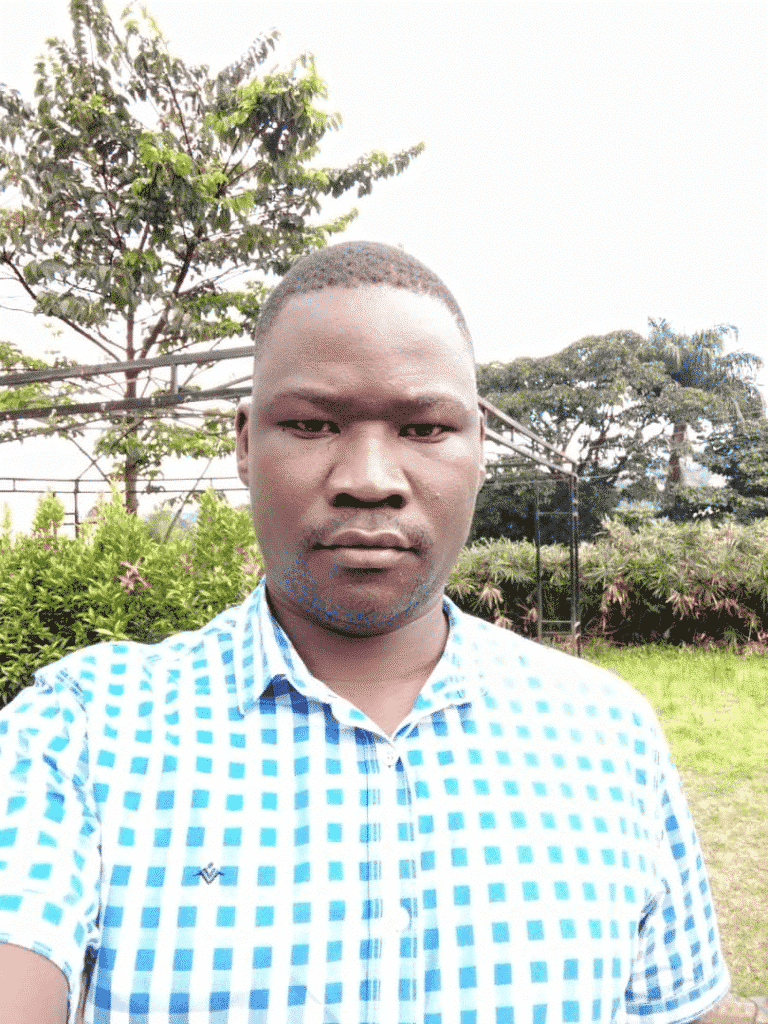

Bojo David Leju: blowing the whistle on South Sudan‘s destructive oil industry

The full story is finally coming out.

How much oil, wastes and toxic chemicals were spilled into South Sudan’s environment by Greater Pioneer Operating Company (GPOC), Dar Petroleum Operating Company and the other consortia and companies forming the country petroleum industry.

How vast and horrible the effects of this poisonous brew have been on the health of South Sudan’s people and environment. How Sudan Sudan’s corrupt government energetically and callously abetted this “eco-cide”. That the fully story is finally coming out is thanks to Bojo David Leju. No one knows better than he the crimes comprising this eco-cide. And that’s because it was his job at GPOC to cover them up.

And now, thanks to Bojo’s courage in documenting these crimes, the world is learning their extent.

And now, thanks to Bojo’s thoroughness and precision of documentation, the millions of victims of this eco-cide have hopes of its being brought to a speedy end, and of their receiving help in rebuilding their lives and regaining their health.

Perhaps it’s time – high time – for the world to say “thank you” to Bojo David, who desperately needs any kind of practical appreciation and help.

His courage in blowing the whistle on South Sudan’s oil industry put him in mortal danger. It got him seized by agents of GPOC, who forced him to recant the testimony on eco-crimes and cover-ups rendered by Bojo to Wani Santino Jada.

Wani is the attorney who is suing – on behalf of the people of South Sudan – the government and oil consortia.

Wani’s lawsuits are now awaiting docketing at the East African Court of Justice. These lawsuits would force the oil industry to immediately halt operations – and the government to pay $720 million in indemnification to the victims of oil pollution.

In July, 2020, Bojo managed to slip out of the house arrest under which he had been placed in Juba, South Sudan by these agents of the government and oil consortia. In a thrillingly bold maneuver, he escaped his jailers and made his way out of the country. Bojo has been in hiding ever since.

He and his family desperately need any and all kinds of support and shelter.

Why did Bojo decide to become a whistleblower, although he well knew – thanks to the examples of Edward Snowden, Julian Assange and others – that it meant risking his life and losing his comfortable job?

“I thought it was better for me to lose my job and perhaps my life than letting the innocent souls continue being enslaved to the oil companies and their harming of lives and the environment,” says Bojo, speaking from his place of refuge.

“I saw that I had a unique opportunity to liberate these people, and to stand with them for the asserting of their rights to clean water and a healthy environment.”

“Oil pollution: spreading like a cancer throughout South Sudan”

In December, 2012, Bojo, a veteran of the oil industry, began what sounded like a a great job: as the engineer in charge of projects of facility and road construction at GPOC’s operations in the Unity oil field in northern South Sudan. As Bojo soon discovered, the reality of his work turned out to be depressing – even horrifying.

“From my first day of work, I was a witness to my company’s willingness to cause oil pollution, and I was a witness to a lack of concern about this pollution’s effects on the environment and on the communities in and around the oil fields,” states Bojo.

The main concern of GPOC turned out not to be preventing oil spills, leaks and fires, or at least dealing with them in effective ways, but, rather, concealing their existence to the outside world.

So Bojo and his team spent much of their working days covering up this poisoning of the environment.

Widespread cover-ups included mixing oil-laden earth with non-contaminated soils, so as to ‘dilute’ the former, and make it less obvious to the naked eye. Or taking contaminated earth and carting it to remote sites. Further damaging activities: channeling water bearing oil and heavy metals and chemical into ditches, and then throwing dirt on top them.

The problem with these cover-ups: triggered by rainfall, the poisons in the earth inevitably seeped into the area’s ground water, from which they made their ways – via wells – into residents’ bodies and on to their fields. Also recipients of these poisons: the Nile, the Sudd (one of the world’s largest wetlands) and other bodies of water.

By 2019, Bojo’s conscience could stand it no longer. He agreed to testify on behalf of the plaintiffs – the people of South Sudan – in the cases being brought by Wani Santino Jada in the East African Court of Justice.

Bojo’s testimony is any environmentalist’s worst nightmare. Rotting pipelines ready to rupture at any times. Ponds designed to retain oil wastes – and regularly overflowing into the environment. Spills and leaks contaminating forests and fields adjacent to communities. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of spills from wellheads and other oil facilities.

“What broke my heart is the sight of the people of South Sudan going about their daily business and not knowing what they were – and are – being exposed to. They often do not know why their babies are being born deformed, why their children’s intelligence is being dulled, why they have such horrible, crippling pain.”

“As a person of conscience, I had to take action. Even if it meant and means losing my life,” concludes Bojo.